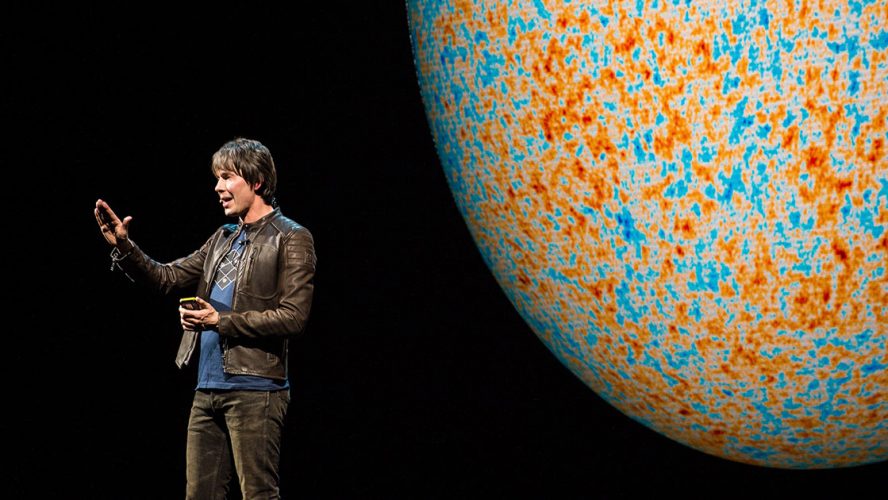

Renowned British physicist Brian Cox blends pop culture and science every chance he gets. On his world tour “Universal Adventures in Space and Time,” the ‘90s rocker discusses the origin and evolution of our solar system and the universe.

Here, the author and co-host of BBC Radio’s science comedy show “The Infinite Monkey Cage 100” shares his scientific and social insights.

You sit at the intersection of science and celebrity, how do you balance your responsibility to both?

Science is too important not to be part of popular culture, by which I mean it must be part of everyday conversation — the zeitgeist, if you like. There is a great deal of competition for our attention: sports, advertising, politics, Facebook. Science must operate within this space if it is to maintain meaningful contact with the wider population; it must fight for attention.

Our civilization is built upon and functions to a large degree because of the outputs of science. Our future will be determined by the rate of acquisition of new knowledge and crucially how we deploy it; by what science we choose to do and how we respond to and regulate new findings and new innovations.

Citizens deserve and require a basic knowledge of what science is, what it can and cannot achieve, and, crucially, how it works and why we should trust it over opinion or gut feeling.

You recently broke the record for most tickets sold for a live science show. Explain the broad appeal of the show.

The live shows are at one level cosmology lectures, dealing with black holes, relativity, and the origin and evolution of the universe. I think these are subjects that many people find intriguing. At a deeper level, the shows are about meaning; about what it means to be human, and to live finite lives on a physically insignificant planet in a vast and meaningless Universe.

What research questions will drive future innovation?

Research is the generation of new knowledge about nature. It is very often the case, unsurprisingly, that understanding more about how the world works leads to great innovations. But knowing exactly what to investigate to trigger some revolution or other is far beyond our capabilities.

All governments and industrialists like to convene committees and direct funding in “useful” directions to solve specific problems. The mysteries of nature are far too rich and far too interconnected for a committee, no matter how learned, to target.

The correct strategy is to let people roam beyond the known and follow their curiosity, at least for some of the time.

You struggled with math in school and have famously said, “Anyone can be a scientist.” What advice do you have for someone who is interested but discouraged by not being a “science person?”

Science is not a natural way of thinking — it has to be learned in the same way one learns to play a piano. The journey, the struggle to train the mind to think in this alien way, is tremendously rewarding and will change your life. If you go on to become a research scientist and discover something new about nature, it may change many people’s lives!

There is no such thing as “not being a science person” — there is only a person who hasn’t practiced.

Staff, [email protected]